Insect Recording at London Zoo

by Ángel Pérez Grandi

On a rainy British summer morning, myself, Phil and Michael met early at the Zoo’s gate, hoping to record bugs for the Sound Collectors Club theme: INSECTS.

For such a metropolitan location finding a café to wait out the rain until opening time was a challenge. Luckily the security guards took pity on us and let us in their cabin, where we had a moment to catch up. I had never met either Michael or Phil in person, so having time to link up in real life was nice after all these years.

We were inside the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), aka the London Zoo. We’d arrived here via an internet rabbit hole, searching for a suitable environment to record insects. We didn’t know what to expect but the Media Liaison person soon welcomed us. In a matter of minutes we were standing in a high-ceilinged warehouse room.

It turns out that the ZSL have a live food department where they breed exotic bugs to feed some of the animals they keep. Furthermore, they were more than happy to show us around and have a go at recording these bugs.

Despite its central location within the Zoo and the less-than-ideal acoustics of the room itself, we were lucky on three counts:

- there were no fans because the bugs require warmth;

- no heaters either as it was summer, and more importantly,

- the main bug species was loud.

On top of this, the breeding expert was really accommodating. He gave us a thorough tour of the various species, answered our barrage of questions and even helped us isolate some individuals for recording.

It felt tropical in there and we were sweating before we even started. The three of us were delighted by the trove though. We exchanged quick glances and got to work without hesitation.

The main species of insect we recorded was the Black field cricket (Gryllus bimaculatis), a common live food for reptiles and pets. This is what they sound like:

Other species included cockroaches and beetles, as well as invertebrates such as woodlice, snails and earthworms.

Michael used his trusty Sennheiser MKH40 (cardioid condenser) for mono insect goodness, Phil brought with him a Neumann RSM191 (Mid-Side stereo shotgun) and a Sanken CUX 100K, renowned for it’s ultrasonic prowess and particularly useful for insects (more on this below). I had packed a pair of DPA 4060s (omnidirectional) mics, because of for their form factor – thinking of getting extreme close ups in small spaces – and because I had an interview recording job in the afternoon.

I’d also packed a pair of Aquarian Audio H2A hydrophones, and I was glad I did.

Insects produce all sorts of interesting sounds, from a sound design perspective: buzzing, chirping, tapping, munching, stridulating, thrumming, to name a few rhythmic ones; but there’s plenty of droning, humming or hissing to be had too. They are also useful for suggestive associations when used in backgrounds or ambience tracks.

Courtship is one of the main reasons that insects produce sound, so a little research into their mating habits goes a long way. Other reasons include territorial behaviour, as warning signals and alarm calls, for navigation and even as a defence mechanism through disguise by mimicking. Such is the case of the Ten-lined June beetle (Polyphylla decemlineata) or hissing beetle, which produces a sound similar to a bat vocalisation and was present at the London Zoo. But we failed to record it.

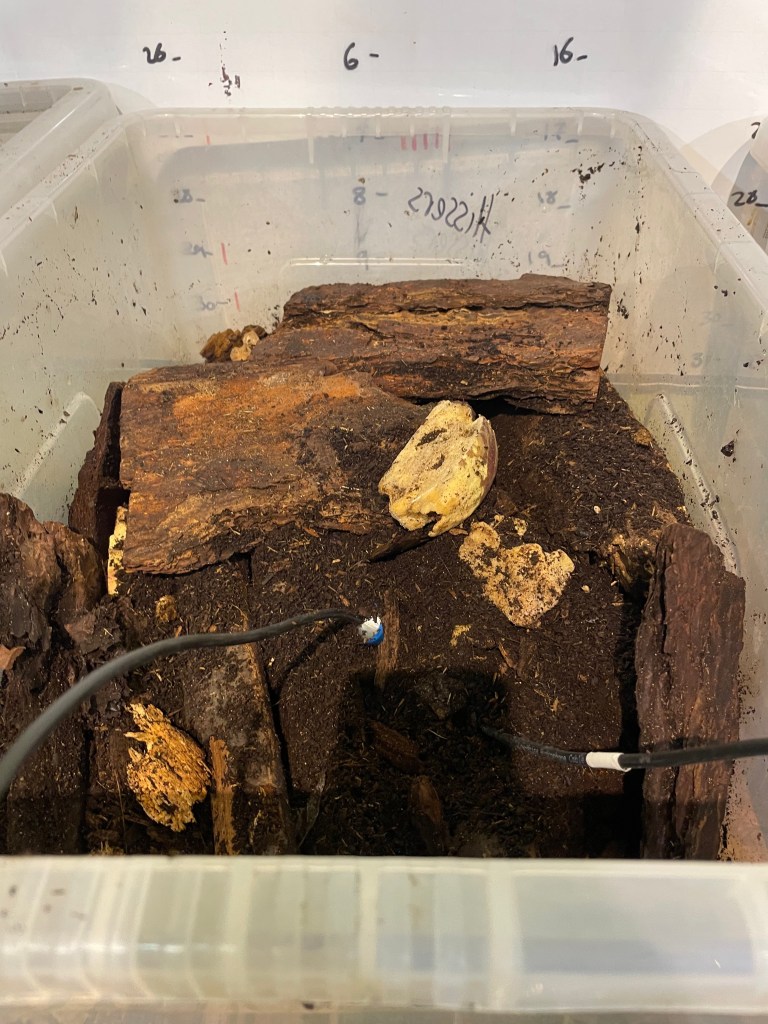

What we did not know and were about to uncover – quite literally – were the sounds produced by beetle larvae, inside decaying soil matter. We buried the hydrophones in one of the breeding boxes that was full with soil and rotting wood, essentially converting them into contact mics. This is what we got:

Why they produce these sounds is still to be fully understood, but biotremology and soil ecoacoustics are growing fields of study. The former is primarily about biological communication via vibrations, while the latter focuses on the study of acoustic and vibrational properties within soil ecosystems.

In this case the ground was soft but out in the field you can get some really experimental sounds by attaching a metal probe to a contact microphone and sticking the probe into the ground. Apparently, this practice dates back to the 70’s when a female member of the Gutai group in Japan began placing microphones underground. In the last couple of decades, UK based sound artist Jez Riley French has been developing these techniques – as well as making contact microphones – for his field recording and creative listening practices.

A great insect to try and record in the summer months are grasshoppers, both individually and as a soundscape. There is something relaxing about the subtle sound of crickets in a meadow. It’s a little more intense in the jungle, but nonetheless useful for our purposes as sound editors and designers.

Another interesting group are aquatic bugs, such as these water boatmen:

With relatively affordable hydrophones (Jez Riley French models, for example) you can record aquatic insects and a whole plethora of other sounds you never thought even existed.

To sum up here are some learnings and tips for recording insects:

- Think inside the box: contact local live food breeders or pet stores in your area, which will usually keep insects in boxes. And use boxes to isolate individuals. This applies in the field as well.

- Go ultrasonic: many species of insects emit sounds at ultrasonic frequencies. Record at high sampling rates – 96 kHz or ideally above. Additionally, use microphones which capture sound beyond the human hearing range (20 kHz) – but don’t be fooled if the microphone specs only cover up to 20 kHz, most microphones will record sound beyond that.

- Go underground.

- Go underwater.

- Try and get an ID as much as possible.

I included this last point because as we have explored there is still much to uncover when it comes to insect sounds and communication. Who knows? You could end up recording a behavioural sound that has not been captured before. You can use apps such as iRecord Grasshoppers which covers all species of grasshoppers and connected species in the UK. For German speakers Orthoptera covers many species in Europe. I’m not aware of what is available for the rest of the world but there are reference websites out there such as https://songsofinsects.com/ for North America, where you can investigate.

Happy recording!

Ángel